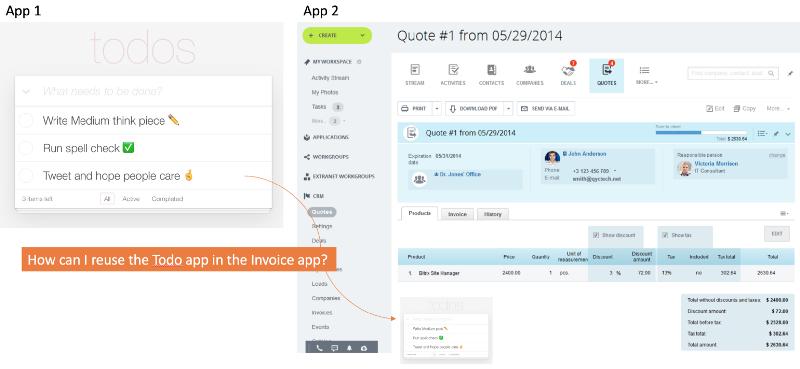

Imagine your team just deployed an amazing todo list app. A month later, another team in your company wants to run your todo app within their invoice app.

So now you need to run your todo app in two spots:

- By itself

- Embedded within the invoice app

What’s the best way to handle that? ?

To run an app in multiple spots, you have three options:

- iframe — Embed the todo app in the invoice app via an <iframe>.

- Reusable App Component — Share the entire todo app.

- Reusable UI Component — Share only the todo app’s markup.

Option 2 and 3 are typically shared via npm for client-side apps.

In a hurry? Here’s the summary.

Let’s explore the merits of each approach.

Option 1: iFrame

With an iframe, you can compose two apps together by placing the “child” app in an iframe. So in our example, the invoice app would embed the todo app via an iframe. Easy. But not so fast…

When is an iframe a good fit?

- Incompatible tech — If the apps you’re composing use incompatible technologies, this is your only option. For example, if one app is built in Ruby and the other in ASP.NET, an iframe allows the two apps to display side-by-side, even though they are actually incompatible and hosted separately.

- Small, static dimensions – The app you’re framing in has a static height and width. Dynamically resizing iframes is doable, but adds complexity.

- Common authentication story – An iframed app shouldn’t require separate authentication. Separate authentication can lead to clunky interactions as the framed app may prompt for separate credentials or timeout at a different time than the hosting app.

- Runs the same way everywhere — With an iframe, the framed app will run the same way in each spot where it’s framed in. If you need significantly different behavior in different contexts, see the other approaches below.

- No common data — With an iframe, the composed applications should avoid displaying the same data. Framing an app can lead to duplicate, wasteful API calls and out-of-sync issues between the framed app and its parent. Data changes in the iframe must be carefully communicated to the parent and vice-versa, or the user will see out-of-sync data.

- Few inter-app interactions — There should be very few interactions between the hosting app and the iframed app. Sure, you can use window.postMessage to pass messages between the iframe and the hosting app, but this approach should be used sparingly since it’s brittle.

- A single team supports both apps — With iframes, the same team should ideally own and maintain both the parent app and the framed app. If not, you must accept an ongoing coordination relationship between the teams that support the applications to assure they remain compatible. Separate teams create an ongoing risk and maintenance burden to maintain a successful and stable integration.

- Only need to do this once — Due to the point above, you should only iframe an app once to avoid creating a significant maintenance burden. The more times an app is framed, the more places you risk breaking when you make changes.

- Comfortable with deployment risks — With an iframe, you must accept the risk that a production deploy of the framed application may impact the parent app at any time. This is another reason having the same team support both the parent and framed app is useful.

Option 2: Share App Component

Node’s package manager, npm, has become the defacto way to share JavaScript. With this approach, you create an npm package and place the completed application inside. And it need not be public — you can create a private npm package on npm too.

The process for creating a reusable component library is beyond the scope of this post. I explore how to build your own reusable component library in “Building Reusable React Components”.

Since you’re sharing the entire app, it may include API calls, authentication concerns, and data flow concerns like Flux/Redux, etc. This is a highly opinionated piece of code.

When is the reusable app component approach a good fit?

- Compatible tech — Since you’re sharing a reusable component, the parent app needs to be compatible. For instance, if you’re sharing a React component, the parent app should ideally be written in React too.

- Dynamic size — This approach is useful if your app’s width/height are dynamic so it doesn’t fit well in a statically sized frame.

- Common authentication story — The two applications should ideally utilize the same authentication. Separate authentication can lead to clunky interactions as each app may prompt for separate credentials or timeout at a different time.

- You want the app to run the same way everywhere — Since API, authentication, and state management are built in, the app will operate the same way everywhere.

- No common data — The two applications mostly work with separate data. Displaying apps side-by-side can lead to duplicate, wasteful API calls as each app makes requests for the same data. It can also lead to out-of-sync issues between the two apps. Data changes in one must be carefully communicated to the other, or the user will see out-of-sync data between the two apps.

- Few inter-app interactions — There should be few interactions between the two apps. Sure, you can use window.postMessage to pass messages between them, but this approach should be used sparingly since it’s brittle.

- A single team supports both apps — With this approach, ideally the same team owns and maintains both apps. If not, you must be willing to accept an ongoing coordination relationship between the teams that support the two applications to assure they remain compatible. Separate teams create an ongoing risk and maintenance burden to maintain a successful and stable integration.

Option 3: Share UI Component

This option is similar to option #2 above, except you share only the markup. With this approach, you omit authentication, API calls, and state management so that the component is basically just reusable HTML.

Popular examples of simple components like this include Material-UI and React Bootstrap. Of course, a reusable app component has more moving parts, but it operates on the same idea.

Before we discuss the merits of this approach, let me address a common question: “Should my reusable components embed API calls and auth?”

My take? Avoid embedding API, auth, and state management concerns in reusable components.

Here’s why:

- It limits reuse by tying the front-end to a specific API, auth, state management story.

- Often, separate developers/teams manage the UI and API. Embedding API calls in a reusable component couples the UI team and the API team together. If one side changes, it impacts the other, which creates an ongoing coordination overhead and maintenance burden.

But yes, this does mean each time someone uses your reusable component, they have to wire up the API calls and pass them in on props.

When is the reusable UI component approach a good fit?

- Compatible tech — Since you’re sharing a reusable component, the parent app needs to be compatible. For instance, if you’re sharing a React component, the parent app should be written in React too.

- Dynamic size — This approach is useful if your app’s width/height are dynamic so it doesn’t fit well in a statically sized frame.

- Different authentication stories — Since this approach is basically just reusable HTML, the apps you want to compose can have different auth stories, or the auth story can differ in each place the component is used.

- Different behaviors in each use case — With this approach, you can reuse a front-end, but call different APIs in each use case. Each copy of the front-end can operate completely differently. You can set different props and hit different APIs in each use case to tailor behavior as needed.

- Common data — With this approach, the UI you’re composing can utilize and display the parent app’s data. It’s a single, cohesive app. This avoids duplicate API calls and out-of-sync issues, saves bandwidth, and improves performance.

- Many cross-app interactions — If there are significant interactions and shared data between the applications, this approach assures that the two applications feel like a single cohesive experience…because this approach creates a single, cohesive app.

- Discoverability is desirable — You want to publicize the existence of a rich, reusable front-end as a component. You can place this component in your reusable component library and document the props it accepts so that others can easily find and reuse it in different contexts.

- Multiple use cases— You plan to deploy this front end in many places. This approach is more flexible than the other approaches since you’re just sharing a highly configurable front-end.

- Separate UI and API teams — If you have a separate UI team, tying the UI to the API via the other approaches is unattractive due to the aformentioned coordination overhead. With this approach, you control when to update the npm package. You can deploy a new version of the reusable front end when desired, on a per app basis.

Summary

As usual, context is king. In most cases, I recommend approach #3, but each has valid use cases. Have another way to handle this? Please chime in via the comments.

Comments are closed.